Forecasting the Lebanese Elections

A rare opinion poll signals a collapse of some traditional parties a few months ahead of Lebanon's general elections.

Earlier this month the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, a German think tank linked with the Christian Democratic Union, published an opinion poll by Statistics Lebanon. The poll, carried out in December 2021, asks respondents their positions on various issues, their personal situation in the context of the economic crisis, and their voting intention for the upcoming parliamentary elections, scheduled for May 15.

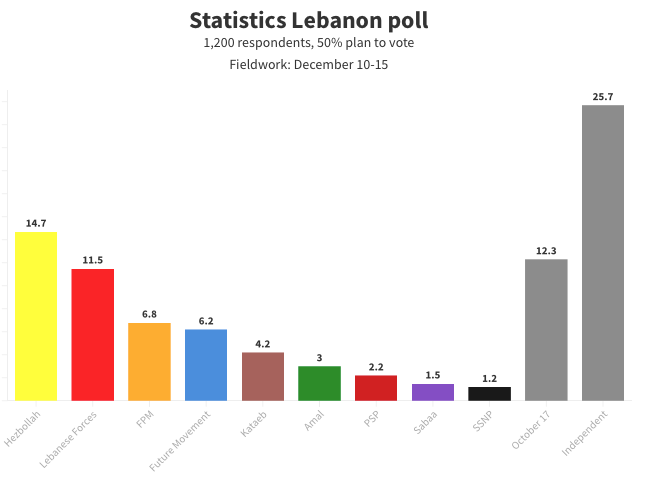

Half of the 1,200 respondents indicated that they plan to vote in the election. Of that half, about 26% said they’ll vote independent, followed by 15% for Hezbollah, 12% for “October 17 uprising/change groups”, referring broadly to the collection of anti-establishment parties that participated in the protests that began in October 2019, and 11.5% for the Lebanese Forces. All other parties are below 10%.

It needs to be noted that voter intention polls are very rare in Lebanon and the accuracy of this is questionable, not just due to potential problems with the sampling, but also inherent issues with how the responses in the poll relate to the Lebanese election system. To start with, “independent” is a very nebulous category and could refer to anyone from a representative of an “independent” anti-establishment party, to a technically independent politician affiliated with one of the main parties. “October 17” is also vague, and could refer to any number of parties, some of which are at odds with each other.

Even putting that aside, polls are not useful for predicting results because of Lebanon’s multi-member constituency list voting system, where parties and candidates ally to make different lists and try to get as many votes as they can in different districts. We don’t know what those alliances will be yet, and there’s no way to predict how many seats each party would win, even if this poll were 100% accurate.

With that said, it is still an interesting look at political attitudes, particularly with regards to the collapse of four of the six main parties—The Free Patriotic Movement, the Future Movement, the Amal Movement, and the Progressive Socialist Party (the other two being Hezbollah and the Lebanese Forces).

The Shiite Duo

Shiite politics in Lebanon has been dominated by the Hezbollah/Amal duo since the 1980s. While initially rivals during the civil war, the parties eventually reached a detente and been close allies since. The two did not compete against each other for any seats in the 2018 election, sharing lists between their candidates and independent and small party allies. Hezbollah received 16% of the vote and Amal and its allies received roughly 11%. Between them they won every Shia seat except one, in Jbeil, where a high Christian population meant Hezbollah’s list was relatively weak and did not win enough votes to pass the seat threshold in the district.

It is necessary to briefly explain the Lebanese electoral system, which is immensely complicated. In short, candidates will come together in a list to compete for all or some of the seats in a district (which varies based on population). There are a certain number of seats per religious sect based on the demographics of the district. Voters will vote for a list, as well as give a preferential vote to a specific candidate on the list. The more votes a list gets, the more seats it wins in the district, and the more preferential votes a candidate gets the higher chance they have to be elected to one of those seats their list won.

Because of their closeness, it is only possible to talk about Amal and Hezbollah together. Hezbollah won less seats than Amal, but greatly outperformed them in the preferential vote, mostly due to the fact that Hezbollah basically allows Amal to win seats. In the South III district, where their joint list won all 11 seats up for grabs, there were seven Amal candidates and only three Hezbollah candidates (plus one SSNP). The three Hezbollah candidates emerged way ahead of their Amal allies in preferential votes. Hezbollah is more popular and could run more candidates if they wanted (thus winning more seats) but chooses not to, because Amal is a useful ally (in part because it’s not a designated terrorist organization by the West).

In the Statistics Lebanon poll, Hezbollah has about 15% of voter intention, within the margin of error of their 2018 result. It wouldn’t be surprising if this were true, the party is not associated with corruption like the other major parties, and its ideological basis makes it much more of a “real” party than the others, which are ruled by families and serve as sectarian clientalist networks rather than something with a real ideological goal. It makes sense that Hezbollah has the most steadfast support because its followers are true believers.

On the other hand, if Amal’s poll result is anything remotely accurate, their support has not held steady at all. Party leader and parliament speaker Nabih Berri was one of the main targets of the protest movement, and even in the South there were instances of Shia demonstrators burning his portrait and tearing down Amal banners. The party has no raison d'être like Hezbollah, and it remains to be seen how long their partner can keep them afloat for. If you look at the combined numbers, the poll result has the duo down almost 10 points from their combined 2018 result. This could open the door for other forces to win seats in areas where they previously dominated.

The Christians

President Michel Aoun and his Free Patriotic Movement are probably the biggest losers of the current situation. In 2018 they were riding high, having trounced their Christian rivals and emerging with the largest bloc in parliament and largest chunk of cabinet seats. Aoun’s son-in-law, Gebran Bassil, succeeded him as party leader and was looking like a serious contender to be the next President (the election to replace Aoun is scheduled for this year, voting is done by MPs). In the years since Bassil has become one of the most reviled men in the country, lacking support from even FPM followers (who are attracted by the figure of Aoun more than anything), Aoun has slipped further into senility, and now they’re being caught up by their rivals.

With Bassil weak, the “March 8” camp may look towards Marada leader Sleighman Frangieh for the presidency. From the other side, Lebanese Forces leader Samir Geagea and even Kataeb leader Samy Gemayel could be contenders. Both the LF and Kataeb have tried to position themselves as anti-establishment, with Kataeb’s three MPs resigning after the Beirut port explosion, and the LF refusing to participate in the current unity government under Mikati that includes all other major parties.

This positioning is obviously farcical, both parties have deeply sectarian histories and are not interested in any kind of progressive reform that could help Lebanon. Their rhetoric has emphasized the issue of Hezbollah’s arms and the supposed need for the state to confront the party over this issue, claiming it’s one of the causes of Lebanon’s crisis (according to the poll, only 8% of the respondents view this as the most important issue at the moment). Kataeb, for its part, has rejected the LF’s posturing, saying they will not form any electoral coalitions with Geagea.

Despite the disingenuousness, the strategy appears to have succeeded for both parties. Again, it’s necessary to emphasize that we have no idea how accurate this poll is, but both have the potential to make gains from their 2018 results. Where they go from there in terms of alliances with other groups I can’t say, their other traditional anti-Hezbollah allies are severely weakened.

The Sunni Vacuum

This poll was conducted several weeks before Saad Hariri announced that his Future Movement will not be participating in the elections. Even before that announcement, it leaves Future down 10 points from 2018, signaling a huge collapse for the party. I don’t know if Hariri has any internal polling of his own and saw the writing on the wall and decided to pass on the upcoming vote, but even if he didn’t, you wouldn’t need a poll to know he’s in a bad spot.

The Future Movement’s collapse and absence from the elections creates an uncertain vacuum in Sunni politics. There is no other national Sunni Party that rivaled Future, and instead it may be traditional regional players that pick up the pieces—Mikati, Karami, Safadi, and Rifi in Tripoli, and Makhzoumi in Beirut, to name a few. There is also the possibility that despite Hariri’s instructions to Future Movement MPs and members to not compete in the elections, some go ahead with it anyway, in the hopes of securing their continued existence in politics.

Another potential player is Saad’s brother, Bahaa Hariri, a billionaire businessman who entered politics in 2019 trying to pick off his brother’s support and claim the legacy of their late father, former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri. Bahaa has criticized his brother for supposedly being soft on Hezbollah, and claims that he will “take back the country”, and “restore sovereignty”. Despite coming from one of the richest families in the country with a deep background in politics, he positions himself as a political outsider, similar to the Lebanese Forces. Like the LF, Bahaa has the favor of Saudi Arabia, who have seen their influence in Lebanon wane in recent years as they cut off Saad for not being as aggressive as they’d hoped. Success for Bahaa’s movement (Together For Lebanon) in the elections would be a continuation of the worst kind of oligarchic, status quo politics, but he may have the money and backing to pull it off.

Besides all of these establishment forces, the protest movement parties may have real success in the Sunni community. Predominately Sunni areas like Tripoli, parts of the Bekaa, and West Beirut saw significant protest activity when the movement was at its height. A lot will depend on how organized “October 17” parties are in coordinating and targeting their efforts.

Other Thoughts

Aside from the fact that we have no idea how accurate polling in Lebanon might be, this poll is frustratingly vague, and a bit weird. My guess is that they provided the list of parties for respondents to choose from, rather than choosing to display the most popular responses, which would be the reason for the Sabaa Party to appear on there. Sabaa is a somewhat shady, well-funded party that was the only “independent” group to win a seat in 2018 (which they later lost when the MP quit the party), and from my perspective at least, I don’t hear as much about them these days compared with say, MMFD or the National Bloc. I find it hard to believe that Sabaa would be the most successful of these anti-establishment parties. Maybe KAS had some ulterior motive to include them specifically, but I would guess it was just because whoever drew the questionnaire up knew they won a seat before.

We don’t get any idea of where people are leaning beyond the traditional parties already represented in parliament, and I doubt we will until the votes are in, it’s just too hard to poll that kind of thing, with dozens of different forces sometimes competing, sometimes allied with each other. What the poll shows probably isn’t any kind of encouraging result for protest movement activists, even though the establishment has been dealt a huge blow, they still have more combined support than genuine progressive, anti-sectarian reformists. But again, can’t put any real stock in this, it won’t reflect the actual results, whichever way they swing.