Bolivia's Other Elections, pt. 1

Subnational elections in Bolivia provide another test of the Movement Towards Socialism's strength

On March 7 Bolivians will go to the polls to elect nine departmental governors and hundreds of mayors and regional and local councilors. Evo Morales’ Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) is the dominant force in the country—it controls six of nine governors and is the only party competing in every municipality across the entire country, from the indigenous Altiplano in the west to the more conservative and mestizo media luna departments in the east. There’s no single party that can overshadow MAS, but in certain places across the country they do face competition from disparate groups.

For those unaware, MAS, or by it’s full name, the Movement Towards Socialism–Political Instrument for the Sovereignty of the Peoples, is a left-wing party formed out of the country’s peasant and trade unions in the 1990s as a political instrument (it’s in the name) for the country’s indigenous population, which makes up a majority of the country and is largely located in the western Andean highlands. Before the 2005 election of Evo Morales, an Aymara, Bolivia had been ruled by a white and mestizo political class that was unaccountable to indigenous Bolivians. His presidency saw massive reductions in inequality and poverty and increases in literacy and healthcare. This success has allowed MAS to remain the dominant party in the 16 years since.

The party has not been without its challenges though. The 2019 presidential election saw Evo Morales get his lowest share of the vote (47%) since being elected, which, while enough to win, was low enough to give Bolivian right-wingers the opportunity to launch a coup with the help of the military under the pretext of unproven election fraud. The MAS government had, for one reason or another, alienated enough voters over the years that they lost their rock-solid majority. Only with the backlash to the coup was presidential candidate Luis Arce able to recover some of that support and win the 2020 election. For further context on the Bolivian political environment I really recommend this piece by my friend Nolan.

Here I will attempt to evaluate where the Movement Towards Socialism stands going into the 2021 subnational elections. Where the potential wins and losses are, what it tells us about the lessons they’ve learned. I’ll also take a look at some of the other political forces in the country, on the left and right, and what they stand to lose or gain.

The system for the election of governors is the same as for the President. If a candidate gets 50% or more of the vote in the first round, or more than 40% with a 10-point lead over their nearest competitor, they win outright in the first round. Otherwise it goes to a runoff between the top two. The mayoral races are decided by simple first-past-the-post.

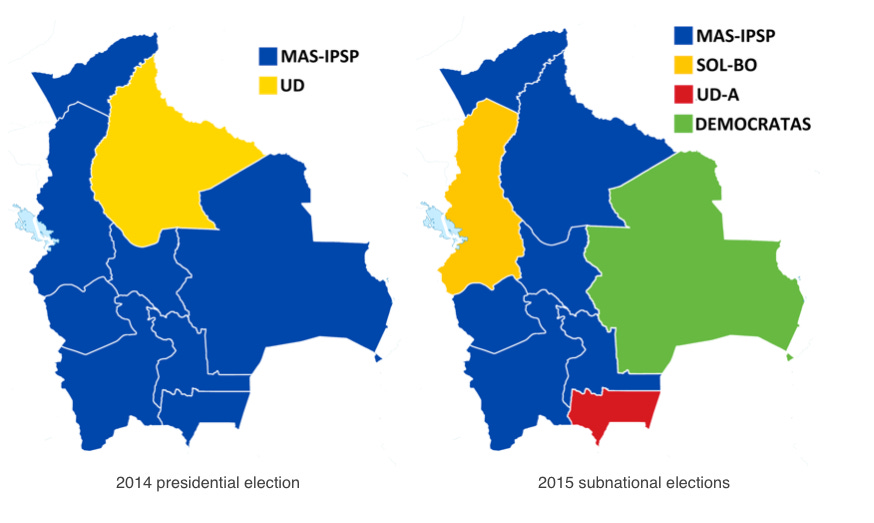

MAS does not have the same level of strength in local and regional elections as it does at the national level. Comparing the 2014 presidential election with the 2015 subnational elections, Evo Morales won 61% of the vote in the former, while MAS only took about 40% of the vote in the latter.

In 2015 MAS won the governorship of the one department it had failed to win in 2014—Beni—but lost three others—Santa Cruz, Tarija, and La Paz. Go back to the elections before those and the discrepancy is still there. Evo Morales won 64% in the 2009 presidential elections compared to MAS’s 50% and 34% in the 2010 elections for governors and mayors, respectively.

Given these numbers, we can guess that approximately 15 to 20% of the Bolivian voter population are “flexible” MAS supporters, without a strong sense of party loyalty towards the party, but who tend to vote for it in presidential elections. There might be a number of reasons for this. Firstly, the lack of another progressive option at the national level. In presidential elections, voters are faced with the choice of MAS or a right-wing candidate. At the local level however, there are more options. Eva Copa’s campaign for El Alto mayor is proving to be a successful example of a leftist non-MAS candidacy (more on that later).

Secondly, voters’ interests aren’t the same at the local level as the national. Maybe you have progressive politics, vote for MAS, but the mayor of your city happens to be from a right-wing party but you like him for some reason, maybe he put in a new road or school. I don’t know to what degree this is the case in Bolivia, but the phenomena definitely exists in countries like Brazil, where party ideology matters very little in most municipal elections.

If this trend holds, MAS can be expected to get around 40% of the votes nationwide, maybe a bit less, on March 7. In the 2019 election, before the coup, Evo got 47%, which went up to 55% with Luis Arce. That’s 8% of the electorate which probably used to vote for MAS, but eventually got dissatisfied with the party and took their vote elsewhere in 2019, maybe to Carlos Mesa, maybe Chi Hyun-Chung, maybe someone else, before returning to the fold after witnessing the racism and authoritarianism of the coup regime.

The question will be: how successfully can MAS use the fact that their old supporters rallied back around them when threatened by the coup to get a strong result in the subnational races? My guess is, not very. There isn’t the threat anymore, no more pictures of burning whipalas to galvanize people. Right-wing politicians in the west of the country, where the most indigenous people live and the MAS is strongest, aren’t using the kind of incendiary, racist language that Luis Fernando Camacho uses to win in Santa Cruz.

Contested races in the MAS heartland

Large cities are MAS’s weak point. The party’s main base is among rural peasants, with urban areas tending to be wealthier, and in some cases whiter. At the national level, MAS dominates in the departments of Cochabamba and La Paz (two of the three largest), but in their eponymously named capital cities, it struggles more, with Arce getting 49% in Cochabamba and 46% in La Paz in 2020, putting him in second place in the latter. They lost the capitals of six departments in 2020, winning only Cochabamba, Oruro, and Cobija (Pando).

This weakness is even worse at the municipal level. MAS failed to win the mayorships of the three main Andean cities in 2015—Cochabamba, La Paz, and El Alto. The last is the most significant. Located adjacent to La Paz, El Alto is Bolivia’s second-largest city, and unlike other urban areas it’s very poor and upwards of 80% of the population is indigenous, making it a strong support base for MAS. Arce won the city with 77% of the vote. But in the last election in El Alto, MAS surprisingly lost the mayorship (their previous mayor had faced major corruption scandals) to Soledad Chapetón of Unidad Nacional (UN), a neoliberal party that has seen some success in western Bolivia by putting on a progressive veneer.

This year MAS faces an opponent of their own making, former Senate President and MAS member Eva Copa. She tried to get the MAS nomination for the position but was snubbed in favor of former mayor Zacarias Maquera. Feeling cheated, Copa left MAS and joined the movement Jallalla La Paz, created by the left-wing peasant leader Felipe Quispe, who has a long history of opposing MAS. Quispe was the frontrunner for the governorship of La Paz before he passed away in January.

Eva Copa seems all but guaranteed to win in El Alto. Polls for the election have had her at over 70% support, with Maquera in a very, very distant second. If these numbers aren’t wildly wrong, Copa’s success represents something of a backlash against the MAS political establishment. Maquera’s nomination is seen by many as a case of “finger-tapping”, by which a powerful individual within the party selects a candidate without respect for the will of the party base. Copa, who became Senate President after the coup when those in front of her in the line of succession resigned, is distrusted by many in the MAS leadership for her more conciliatory approach to working with the Jeanine Áñez government.

Evidently though, she’d still popular enough with the local party base that when her candidacy was rebuffed, supporters still flocked to her after she changed parties. Copa is in the unique position of being able to attract progressive voters that ordinarily support MAS as well as anyone-but-MAS voters who will back any candidate that can beat the party they hate. The Copa case is an interesting reflection of the flexibility of MAS support. This isn’t just the 15 to 20% of the population discussed above, this is a majority of their base in El Alto that seems to have abandoned the party. If she does have as big a win as polls suggest, it should be a warning sign to MAS that they can’t ignore the will of the grassroots without risking further hemorrhaging.

Next door in the city of La Paz, the race is a bit closer. MAS has never won the mayorship of La Paz, having been defeated in the last two elections by Luis Revilla, founder of the Sovereignty and Liberty party (SOL.bo). Revilla is something of a regional powerbroker. He was elected in 2010 with the Movement Without Fear (MSM), a centre-left party that was allied with the MAS before eventually splitting from them. Revilla founded SOL.bo after the MSM dissolved in 2014. Despite his roots in a progressive party and some posturing that nods toward the left and working class, Revilla backed Jeanine Áñez’s presidential run in 2020, breaking with his former ally, Carlos Mesa, who represents a more moderate right than Áñez.

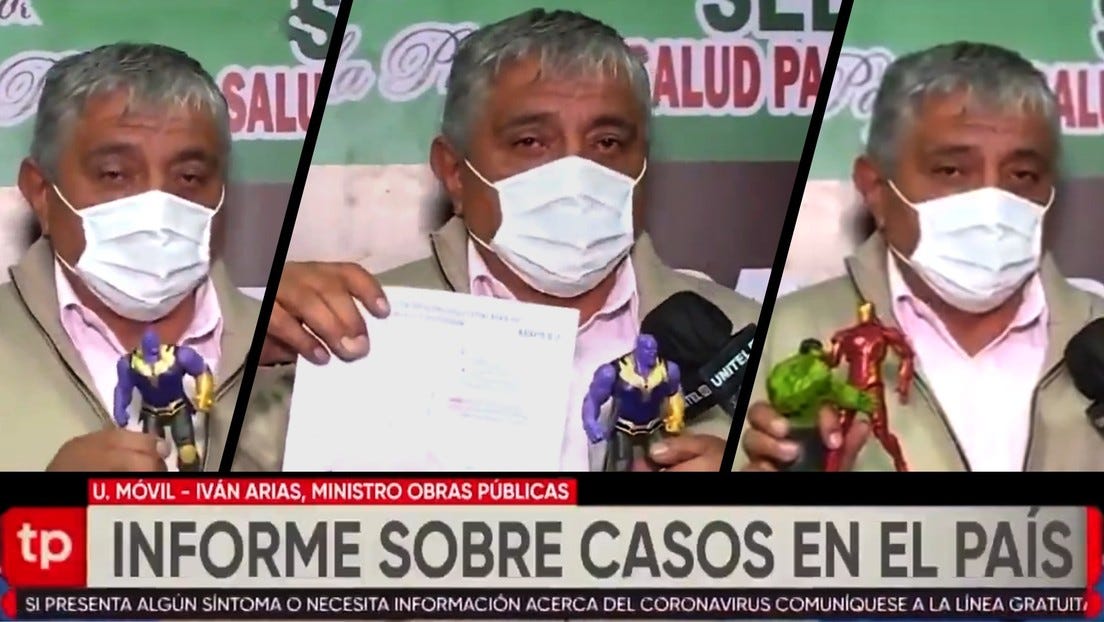

However, a SOL.bo candidate does not appear to be in play this year. Leading the polls for La Paz mayor is Iván Arias, who served as Public Works minister in the Áñez government. Arias grabbed headlines last year for using a Thanos action figure to make an analogy to the coronavirus. He’s been behind a number of other more goofy stunts, but his time in the ministry also saw him embroiled in scandal and making attacks on journalists.

Arias is running with the alliance Somos Pueblo, set up by another member of the Áñez government, Rafael “Tata” Quispe (not to be confused with Felipe Quispe), a right-wing indigenous politician who’s strongly opposed to the MAS. Quispe himself is running for governor of La Paz with SP. Arias also has the backing of Carlos Mesa’s Civic Community, which withdrew their candidate to consolidate the anti-MAS vote after a poll from January showed MAS candidate César Dockweiler in the lead.

Luis Revilla himself is not running for re-election, but has not endorsed Arias. SOL.bo is running their own candidate (polling in the low single digits) and Revilla has publicly feuded with Arias over the course of the campaign, calling him a liar and even leaking Arias’s cell phone number and WhatsApp conversations between the two.

It’s classic Bolivian right wing infighting, with different regional players jockeying for power with each other. There’s no national opposition movement to MAS, only disparate parties and figures who want to keep their own influence. Most of these parties don’t even compete in every department in the subnational elections. SOL.bo is only in La Paz, the Democrats party (MDS) that Jeanine Áñez formerly belonged to mostly runs in Santa Cruz, while Unidad Nacional is limited to the west of the country.

We can see this fragmentation at the national level with the 2020 presidential election. Arce originally faced three major candidates from the right—Carlos Mesa, representing a neoliberal but culturally moderate politics that includes indigenous and environmental activists dissatisfied with the MAS, Luis Fernando Camacho, representing hardline, far-right interests from Santa Cruz, where Christianity and cattle ranching reign supreme, and Jeanine Áñez (who would eventually drop out), sitting somewhere in between them. All of these candidates had to form alliances behind them as no one party is strong enough to carry a presidential candidacy to oppose MAS. When Áñez dropped out, her backers—Democrats, UN, and SOL.bo—lost out at any chance of congressional representation.